By Dr Niamh Kirk

This year’s digital news report Ireland once again highlighted the on-going worries over misinformation with 62% of people surveyed saying that they are concerned about misinformation online. Two years ago, a range of digital media companies such as Facebook, Twitter, Google and Microsoft signed up to the EC Code of Practice on Disinformation. The European Regulators Group for Audio-visual Media Services (ERGA) is the body responsible for monitoring and supporting the implementation of the code. In Ireland the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland is the national regulator and commissioned Code Check, a report conducted by researchers at the Institute for Future Media and Journalism assessing compliance with the code. It aimed to review the implementation of commitments to empowering users and enhancing media literacy in Ireland by Facebook, Google, twitter and Microsoft. CodeCheck specifically examined the commitments under Pillar D of the code to support users, and Pillar E to support the research community over a 12-month period. [1]

Overall CodeCheck found that the adoption of the Code of Practice on Disinformation by Facebook, Google, Twitter and Microsoft among others was a significant development in the fight against disinformation in Europe. It introduced additional regulatory oversight over the operation of these platforms at a national and European level. However, much more information is needed to ensure that users can evaluate the content they see. The report found significant weaknesses in terms of the content and structure of the code as well as the nature of the efforts by digital media companies to meet commitments to support users and researchers.

Supporting Users

The aim of Pillar D in the Code of Practice on Disinformation is to help people to make informed decisions when they encounter online news that may be false or misleading. Among the issues that digital media companies were asked to address were their commitments to develop and implement effective indicators of trustworthiness, to prioritize relevant authentic and authoritative information in news feeds as well as offer tools to report fake news, to present a diverse range of perspectives, give tools to consumers and inform them on how they can control and personalize the use of their data.

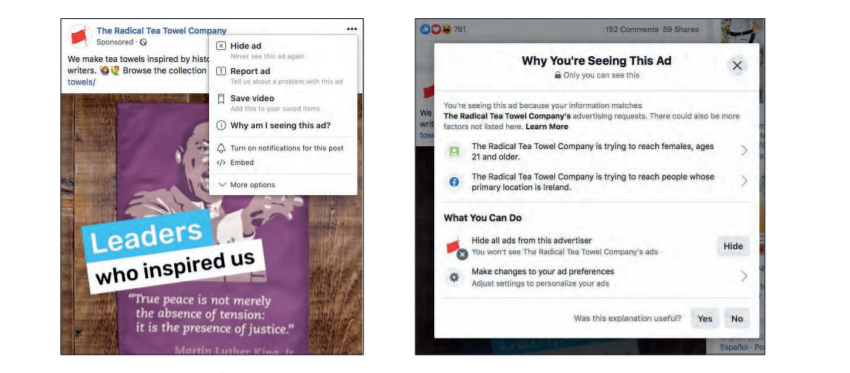

Immediate, ‘on screen’, supports for Irish users was mixed across the code signatories. The signatories provided a range of tools and information portals such as buttons to report misleading information. However, it is not clear how often these features are employed by Irish consumer’s, what actions were taken by them or what actions were taken on the basis of these complaints. It is not clear how many posts were removed, if any. Consumers are slightly better supported regarding the use of their personal data, but the information provided to users is insufficient to be considered highly transparent. For example, exactly what users’ personal data is collected and how it is used in microtargeting remains unclear. Neither Twitter, Google or Microsoft inform users of what specific personal data is used to direct a specific advert to their feed but they do offer some general information.

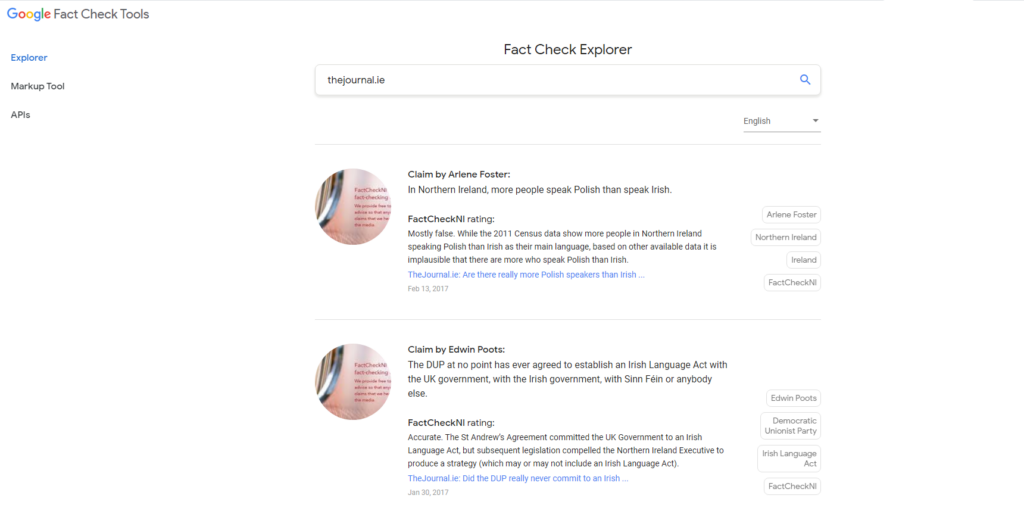

Similarly, Irish users are not well supported in terms of being informed of misinformation in circulation online. This was found to be the most significant short coming in the implementation of the Code in Ireland. While Facebook and Google claimed to label fact-checked content, no fact-check labels could be identified by Code Check researchers across any platform despite nearly 49 fact-checks being conducted by the only IFCN approved fact-check organisation, TheJournal.ie over the time period. Neither Twitter nor Microsoft made any efforts to label content that might be misleading at all. It also remains unclear who is responsible for adding these labels (the Signatories or the fact-checkers) so that users can see that a claim has been reviewed.

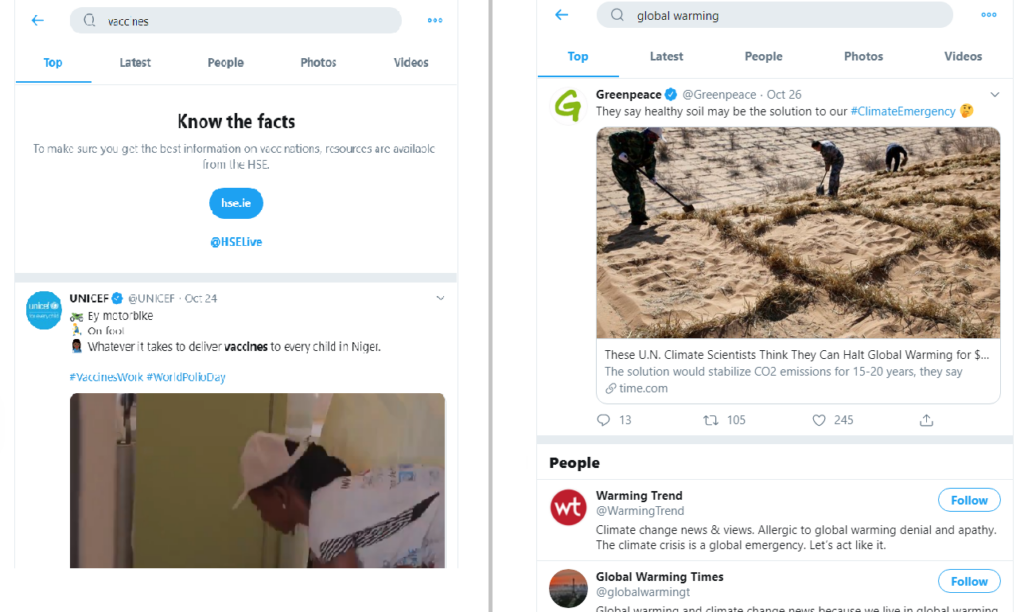

In terms of the presentation of authoritative information, the researchers found that it was inconsistent across and within platforms. For example, while Twitter preformed better than others in this regard, some problems persist. While users are provided with authoritative sources when searching Twitter for health-related information such as ‘vaccines’, when other contested and more politically relevant terms such as ‘global warming was searched , authoritative sources where not prioritised at the top of the search results.

Media Literacy

Similarly, support efforts aimed at improving critical thinking and digital media literacy were lacking. In general, the signatories’ approach to media literacy was to support other organisations, rather than provide information themselves.

For example, Facebook, Twitter and Google are all members of Media Literacy Ireland (MLI). Facebook is represented on the MLI Steering Group and hosted the first MLI conference at their offices in Dublin. Facebook also supported the ‘#BeMediaSmart’ campaign with free ad credit for non-profit MLI members. Twitter similarly supported the #BeMediaSmart initiative with free ad credit for non-profit/charitable members of MLI and has presented at MLI conferences and events. Google has not directly participated in the Working Groups or specific events although it did sponsor the development of the Be Media Smart campaign micro-site.

Google also provided a €1million grant to Irish children’s charity Barnardos. A recent initiative the collaborative project aims to “enable children in Ireland to interact safely and responsibly online”.

However, other efforts by Google were not implemented in Ireland, such as YouTube Creators for Change, Be Internet Citizens and Be Internet Awesome. Microsoft did not report on any Irish specific initiatives or partnerships to support critical thinking and digital media literacy. It does sponsor NewsGuards’s digital media literacy program in Europe, however, Ireland is not one of the countries in which NewGuard is currently available.

Each of the four Signatories to the Code did support some efforts to promote digital media literacy in Ireland both through their interaction with Media Literacy Ireland (MLI) and online initiatives. However, in the absence of any data on the uptake and impact of these initiatives provided by the signatories it was not possible for the researchers to evaluate their effectiveness.

Regarding commitments to help the research community, Pillar E which aims to enable privacy-compliant access to data for fact-checking and research activities CodeCheck found that “supports in place for Irish research and academic institutions were episodic and largely inadequate to assist in the delivery of any rigorous analysis and monitoring of online disinformation trends in Ireland.”

The outcome of CodeCheck and other similar research reports across Europe could contribute to the improvement of the EC Code of Practice on Disinformation. However, any developments depend on the willingness of the voluntary signatories, Google, Twitter, Facebook Microsoft and others to disclose much more information than they currently are and to support users in a comprehensive and meaningful way.

[1] Commitments under Pillar A-C were addressed in previous report Elect Check 2019 and as part of Code Check 2020.

You can read the CodeCheck report which carries analysis of commitments under pillars A, C, D and E of the Code of Practice in full online at FuJomedia.eu and the previous ElectCheck report which addresses commitments under Pillar B, Political Advertising.

Dr Niamh Kirk is a researcher at DCU’s Institute for Future Media and Journalism (FuJo) where she works on projects relating to journalism, social media, information politics and transnationalism. She is a post-doctoral researcher in UCD examining post conflict European societies and a lecturer in Dublin City University’s School of Communications.